YAKIMA, Wash. -- The J.C. Penney auto center has stood vacant for nearly two decades, a symbol of downtown Yakima’s past as the region’s retail center.

It won’t be vacant for much longer: Single Hill Brewing will open a brewery and taproom this summer at the building at 102 N. Naches Ave.

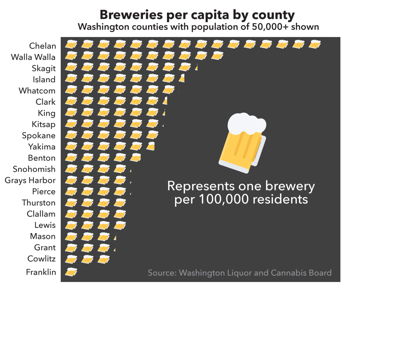

It’s the latest in what has been an explosion of craft breweries that have opened in the Yakima Valley over the past few years. Yakima County is now home to 14 licensed breweries, according to the state Liquor and Cannabis Board. Add in breweries in Benton, Kittitas and Klickitat counties and you have more than 30 breweries within easy driving distance.

That’s a critical mass of breweries. No longer are local fans of craft beer required to drive to cities such as Bend, Ore., Portland or Seattle.

And it’s not just the quantity — the beer tastes good, too.

“The overall quality compared to 30 years ago is tremendous,” said Ralph Olson, who spent 34 years working with breweries as a hop supplier. He still sells hops part time and keeps track of the local brewing scene. “People are brewing a lot better quality beer.”

But stiff competition for grocery shelf space, bar taps and funds from beer drinkers has some asking whether there’s a sufficient market for all these breweries, especially those that want to grow.

“A lot of craft breweries have become larger across the U.S.,” Olson said. “But the market is only growing so much.”

That concern is based on slowing growth in the craft beer industry. In 2016, production nationwide increased by 6 percent year over year, to 24.1 million barrels, according to the Brewers Association, a craft beer trade association. What would be robust growth for other business sectors is considered a notable slowdown for craft beer after years of double-digit percentage growth.

Ty Paxton and Zach Turner, co-owners of Single Hill Brewing, are aware of the trends. Their confidence is based on extensive market research, which showed that not only was there a market for existing breweries but there was room for even more, especially ones that tapped into underserved markets — such as beer drinkers who may not care for the numerous varieties of the hop-driven Indian pale ale that most breweries sell.

“We’re far from saturated,” Turner said. “But more market development is needed.”

Talk of potential oversaturation is in stark contrast to a decade ago, when many lamented the lack of breweries in a region that grew the hops essential for IPAs and other popular varieties.

Back then, there was just one brewery in the county: Snipes Mountain Brewery in Sunnyside. And there were only a handful of breweries in neighboring counties, including Whitstran Brewing in Prosser and Iron Horse Brewery in Ellensburg.

When Yakima Craft Brewing opened in 2008, making it Yakima County’s second brewery, founder Jeff Winn expressed hope that others would join him.

“We respect wineries, but where are the Washington Beer Country signs?” Winn asked in a 2008 Yakima Herald-Republic article.

It would be another few years before the local craft brewery scene would take off, starting with the opening of Bale Breaker Brewing Co. in Moxee in 2013.

“Bale Breaker basically succeeded taking over Eastern Washington; it was an underserved market. (The brewery) just filled that gap, and that’s allowed them to spread beyond that,” said Kendall Jones, publisher of the Washington Beer Blog.

Indeed, Bale Breaker is all over the Northwest and has caught national attention and recognition. And the brewery’s reach looks to increase even more — the brewery completed a major expansion in 2016 that will enable it to produce upward of 30,000 barrels annually in the next several years.

The Brewers Association states that a majority of Americans live within 10 miles of a craft brewer. That’s now the case locally, with new breweries opening as far north as Naches and Cowiche, as far south as Sunnyside and points in between.

There are now enough breweries in the Yakima Valley and other nearby areas to easily fill up the “local beer” tent at the annual Fresh Hop Ale Festival, which promotes beers made with freshly harvested hops.

Industry experts say the number of breweries that the Yakima Valley can support depends on how much they want to grow. Most craft breweries start — and remain — small. Out of more than 5,200 craft breweries, about 96 percent are either microbreweries — which produce fewer than 15,000 barrels annually — or brewpubs, breweries that sell 25 percent or more of product on site.

Bale Breaker Brewing Co. and Iron Horse Brewery in Ellensburg are considerably larger, putting them in a small group of what are known as regional breweries, those that produce more than 15,000 barrels annually. As of the end of 2016, there were 186 regional craft breweries in the U.S., according to the Brewers Association. These are the breweries that have strong regional — even national — brand recognition, the ones you would find on grocery shelves and metropolitan sports arenas.

There’s not much room if all these local breweries want to be regional breweries.

“If you’re focused on trying to be the next Bale Breaker or Iron Horse, you have a tough job,” Jones said.

That’s because there’s stiff competition to get on the inventory list of distributors and stocked on grocery store shelves, including from craft breweries now owned by multinational corporations. Getting space at a grocery store shelf often comes at the expense of another brewery.

“There is only so much beer that’s going to sit on the shelves at the grocery store,” Jones said.

Becoming a larger craft brewer isn’t the only means to success, he said. Realistically, most breweries will see sufficient success producing a few hundred barrels annually to serve to customers at a brewery taproom or at a handful of restaurants and bars.

Jones noted a recent report from MillerCoors, which owns several international beer brands, stating that brewpubs and brewery tap rooms make up about 9 percent of all bar traffic nationwide. In metropolitan areas with a critical mass of craft beer drinkers, such as Seattle and Denver, that percentage is upward of 22 percent and 35 percent, respectively.

That’s why Single Hill Brewing is putting a lot of its focus on its taproom.

Paxton points with pride to one corner of what will become the brewery’s taproom that’s will serve as a kids’ area. Paxton’s wife is set to give birth to a boy next month, and co-owner Turner has a 14-month-old daughter, so there was little question that the taproom would be child-friendly.

The taproom will also include a television screen for those looking to watch games, and there is work being done to convert the concrete and asphalt around the building into outdoor seating and green space.

“We want to make sure we cater to all of the crowd,” Paxton said.

Single Hill Brewing, once it starts production, is aiming to brew 800 barrels of beer this year. Most of the beer will be sold at the taproom, with a small percentage self-distributed to a few restaurants and bars.

A lot of Single Hill’s focus will be to make beer that would draw customers to its taproom regularly. Along with IPAs, which remain quite popular, the brewery has plans to add a regular rotation of experimental beers for adventurous customers and lighter beer varieties for those who might not visit a craft brewery otherwise.

You won’t find Single Hill beer at a grocery store, at least for now.

“It’s pretty difficult to get into any grocery lineup where it would make sense financially,” Paxton said.

But Paxton also said the brewery will have the capacity to produce up to 5,000 barrels annually. In a few years, there may be a need to expand distribution beyond the taproom.

“We’re flexible to the growth of our business,” Paxton said.

(0) comments

Comments are now closed on this article.

Comments can only be made on article within the first 3 days of publication.