-

Stop lurking! Log in to search, post in our forums, review beers, see fewer ads, and more. — Todd, Founder of BeerAdvocate

Stop lurking! Log in to search, post in our forums, review beers, see fewer ads, and more. — Todd, Founder of BeerAdvocate

A Nanoblendery Grows in Belgium: New Stirrings in the Old World of Lambic Beer

Illustrations by Jayde Perkin.

Illustrations by Jayde Perkin.

Just before a lavish rare beer charity auction in Portland, Ore., Jessica Elkan, director of development for New Avenues for Youth, a nonprofit committed to preventing youth homelessness, learned that a surprise visitor was coming. And he had a last minute donation. “Raf bought a hard suitcase and filled it with as many bottles as he could fit,” she says. He flew in standby from Belgium, escorting 10 3-liter jeroboams of his assorted Bokkereyder Lambic creations. Auctioned off separately, the winning bids for his coveted cargo added up to $21,000. Among hundreds of donated rare beers, those 10 bottles from a young operation few have even heard of accounted for nearly 10 percent of the annual auction’s revenue.

Raf Souvereyns lives near the picturesque city of Hasselt, Belgium. East of Brussels in the province of Limburg, it’s well beyond the Zenne River Valley, the traditional heart of Lambic brewing. He calls his young blendery Bokkereyder, a Flemish word that means one who rides a billy goat. It’s a nod to folklore in his father’s hometown that evokes themes of rebellion, or perhaps dark magic. There’s no Bokkereyder taproom to visit, no marketing to speak of, no online T-shirt emporium, only a small private barrel warehouse in a region best known for orchards and vineyards.

His journey to beer is a familiar tale with an Old World twist. Souvereyns first took an interest in touring little-known local wineries. “Belgian wine is not a thing in the world,” he says with a laugh. But he has a strong affection for these winemakers, practicing their craft in obscurity a few hours drive from renowned German and French wine regions. Without plans to make it a career, he helped as an “apprentice” to better understand winemaking.

Next, he ventured further afield in search of artisan products, exploring the classic Lambic beers of the Payottenland region. To some Belgians, these sour beers are relics, the beer of rural grandparents and international tourists. Souvereyns, however, didn’t hesitate to explore and embrace the funky delicacies produced via spontaneous fermentations by airborne microbes. Then he learned it was possible to make these beers not by homebrewing them, but by purchasing authentic young Lambics to blend at home.

Souvereyns was mentored by a fellow amateur blender—quite improbably a German who lives outside Dusseldorf, a large city about two hours East of the Payottenland by car. “Uli is my source of inspiration. It’s all his fault,” says Souvereyns, adding that while their processes differ, he and Uli Kremer have become close friends and allies.

Kremer, a self-taught blender who honed his skills by sharing his experimental concoctions with legendary Lambic producers, is currently pursuing his own commercial blending projects under his Huisstekerij H.ertie label. He remembers coaching Souvereyns during a visit to one of Belgium’s best-known blenderies. “I gave him a tour of the geuzestekerij Drie Fonteinen and I explained everything about Lambic,” Kremer recalls matter-of-factly. Souvereyns says the two visitors started talking in the simple gift shop that day in 2008. Then, as they sampled the ripening barrels in a tour of the compact cellar, Kremer gave him a crash-course in blending and fermentation fundamentals.

In 2013, Souvereyns made his first bulk Lambic purchase. Then 28 years old, he hefted a small used barrel gifted to him by a local winemaker into the trunk of his “really small” car. He then drove to Brouwerij Girardin in Sint-Ulriks-Kapelle and asked to simply fill the barrel in place. Happily driving home, he didn’t anticipate the challenge of getting the 30-gallon barrel—now weighing more than 300 pounds—out of his trunk. But his adventures were just beginning. When a friend reported a backyard sour cherry tree was ready for picking, Souvereyns jumped at the opportunity to create a traditional Oude Kriek for his first project. “It was god-awful, that beer,” he laughs. “It was undrinkable.”

In 2013, Souvereyns made his first bulk Lambic purchase. Then 28 years old, he hefted a small used barrel gifted to him by a local winemaker into the trunk of his “really small” car. He then drove to Brouwerij Girardin in Sint-Ulriks-Kapelle and asked to simply fill the barrel in place. Happily driving home, he didn’t anticipate the challenge of getting the 30-gallon barrel—now weighing more than 300 pounds—out of his trunk. But his adventures were just beginning. When a friend reported a backyard sour cherry tree was ready for picking, Souvereyns jumped at the opportunity to create a traditional Oude Kriek for his first project. “It was god-awful, that beer,” he laughs. “It was undrinkable.”

With renewed determination and an obsessive dedication to quality, subsequent batches went much better. And since then, Souvereyns has been creating Lambic-based beers that make even the most ardent traditionalists take notice—if they can get their hands on a bottle.

At one time, Lambic beers were refermented on fruit or bulk-aged for eventual blending into a three-year Gueuze. This took place in Lambic breweries, but also in beer cafes and dedicated blenderies or geuzestekerij. But as demand for the style began to plummet a century ago, most Lambic breweries vanished, along with the bulk of the ecosystem of independent blenders. Much of the sensory knowledge traditionally passed from person to person has also been lost.

Blending isn’t a simple matter of making a mixture to taste, but a strategic calculation of which elements will—or won’t—taste better after refermenting and conditioning. Any new commercial blending operation battles this learning curve. They also must endure many months without any product to sell, resisting the urge to release beers too young, or to blend bad barrels with good ones to recoup costs.

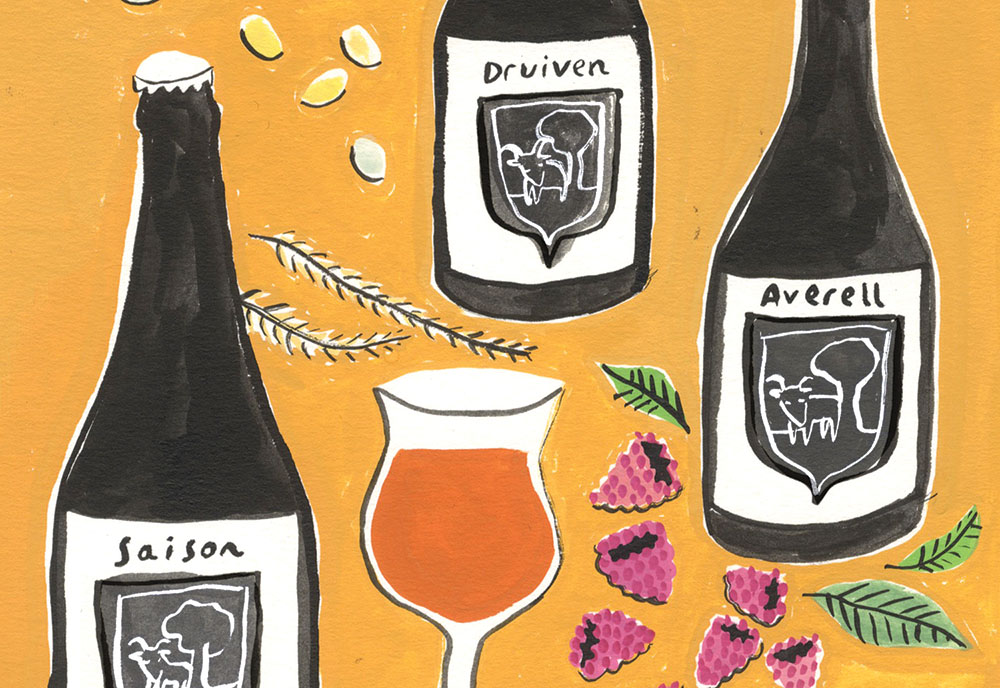

Souvereyns combines three inoculated wort components for all of his beers, relying on relationships with three Lambic producers: Girardin, Lindemans (in Vlezenbeek), and De Troch (in Wambeek). In particular, he believes the De Troch influence is key to his flavor signature. “De Troch is one of those breweries that is so underrated. The Lambic [it] makes is phenomenal but people only relate that brewery to sweetened products,” he laments, referring to quickly-produced fruit beers which subsidize the old brewery’s limited Oude Gueuze production.

Pauwel Raes and his wife Kristel Schelfthout have operated De Troch, the small brewery his family built in the early 1800s, since 2013. And Raes agrees that De Troch fermentations are distinctive. Part of the reason might be that he uses aged New World hop pellets rather than aged whole-cone Noble hops. “We are the only Lambic makers with that much citrus in our Lambic,” he says, adding that he only sells to a few smaller blenders, due to his limited interest in growing his production to make beers for others. He’s also concerned about the age of his equipment. “I don’t want to make 10 or 15 brews more a year for someone else,” Raes explains.

Souvereyns got to know Raes by purchasing small portions of De Troch Lambic. He now buys full batches of inoculated wort out of the brewery’s antiquated, narrow twin coolships. With Bokkereyder’s slow rate of growth, he’s not concerned about outgrowing his suppliers.

Bokkereyder beers range from reverently traditional to boldly inventive. While his Framboos is a classic raspberry Lambic, 2018 will mark the first appearance of a cinnamon raspberry version, which will join an acclaimed lineup including vanilla bean and Cognac barrel-aged Framboos variations. Another series is based on refermented Saison. Without a brewhouse to make a Saison, Souvereyns hooks up his trailer and drives south to buy beer from tiny Brasserie Fantôme in the rural town of Soy. He then adds his three-source Lambic mixture to dry out the Saison and contribute additional complexities.

Chris Lively, proprietor of Ebenezer’s Pub in Lovell, Maine, first tasted Bokkereyder at Yves Panneels’ famous Payottenland Lambic bar, In De Verzekering Tegen De Grote Dorst, currently the only place in Belgium where the beers are sold. He was quickly impressed. As a long-time Lambic expert and aficionado, Lively immediately struck up a conversation with Souvereyns about bringing the beers to Maine. “It’s like going and seeing a great tattoo artist that does portraits, and every single dot of ink that goes into your arm is meant to be there,” he marvels. “That’s not easy to do with Lambic.”

Bokkereyder beers don’t stay in stock long at Ebenezer’s, well over an hour’s drive northwest of Portland. Nor do they last long at the events where they occasionally make appearances. Currently, Souvereyns distributes exclusively through festivals and a handful of beer bars.

Ebenezer’s is the only such spot in the US. At Mikkeller’s Copenhagen Beer Festival in May 2017, Souvereyns and a coterie of volunteers dispensed roughly 10 percent of his annual production during four half-day sessions, pouring two small-batch blends at a time to a long double line of appreciators. He’d like to have his beers in more places, hinting that he’s in talks with more bars in the States, but his limited production is constrained by the number of barrels with mature beer in them. Over the summer, he increased his total to 120. He was also finally able to invest in a forklift. Working full time, alone except for rare assistance from his mother or a friend, Souvereyns is determined to give his beers as much time as they require.

While most connoisseurs haven’t tasted a beer from Bokkereyder, its very existence is a harbinger of larger changes in Belgium. According to Kristof Verhasselt, 38, a board member of Payottenland’s beer consumer organization, De Lambikstoempers, a new wave of demand for Lambic is on the horizon. Younger drinkers in the region tend to favor Oude Krieks and Oude Gueuzes over the aged flat Lambics. Just south of Brussels, around the town of Beersel, in particular, Verhasselt sees a revival of interest. “They know the tradition and appreciate it, but most of all, they like to drink it,” he observes.

While most connoisseurs haven’t tasted a beer from Bokkereyder, its very existence is a harbinger of larger changes in Belgium. According to Kristof Verhasselt, 38, a board member of Payottenland’s beer consumer organization, De Lambikstoempers, a new wave of demand for Lambic is on the horizon. Younger drinkers in the region tend to favor Oude Krieks and Oude Gueuzes over the aged flat Lambics. Just south of Brussels, around the town of Beersel, in particular, Verhasselt sees a revival of interest. “They know the tradition and appreciate it, but most of all, they like to drink it,” he observes.

In late August, members of De Lambikstoempers attended the launch of Lambiek Fabriek in Payottenland, a new Lambic brewery founded when sourcing inoculated wort made by others became too costly and inconvenient for a fledgling blending operation started by three friends. According to Verhasselt, the inaugural beer, Brett-Elle, was markedly young but nevertheless exciting. “I’m very glad that there are some new guys in town and that the products they make (Brett-Elle, Belgoo Bikske, and Den Herberg Lambic) are of a good quality,” says Verhasselt.

“Let’s hope this new wind stays, so Lambic making and blending will never die.”

And then there is the growing number of amateurs, purchasing containers of Lambic to age with fresh fruits at home. Verhasselt can name a handful of them—including himself. And he, too, turned to Uli Kremer, the German Lambic fanatic who frequents De Lambikstoempers events, for tips. “I asked him for some advice about my own blending and got the most important advice: to experiment and learn from my mistakes and victories,” Verhasselt says. “That’s how Uli works.”

But for all of its acclaim, Verhasselt hasn’t yet tasted anything from Bokkereyder either, partially due to the price tag the beers carry. Souvereyns is aware that his Lambics exceed the five to 10 euros that’s the accustomed price range for a good 750 milliliter bottle of everyday Oude Gueuze in Belgium. “It’s sometimes hard for people to justify buying bottles of my beer for 45 euros at Yves’ bar,” he sighs. “It’s a very steep price by Belgian standards.”

By way of justification, Souvereyns says that his production costs alone actually exceed the retail prices of other Gueuzes. This is in part due to his insistence on dumping beer that develops in a direction he doesn’t like. His dedication to local fruit pushes his costs even further. “I am one of the only ones using fresh picked Belgian raspberries,” he insists, noting that others buy berries from Serbia. In fact, Souvereyns sets out with his trailer at 5:00 a.m. to go to the farm on harvest mornings, tenderly collecting soft, “slightly overripe” fruit for maximum flavor impact, dumping them into the tank on his trailer, and rushing home by noon to pump Lambic onto the oozing berries.

Meanwhile, another upcoming Bokkereyder project brings Souvereyns closer to the winemaker’s world again, as he ferments local Chardonnay grapes with 10 percent Lambic. Two of the bottles that rocked the annual rare beer auction in Oregon were examples of what Souvereyns calls Lambic wines. He knows of no other producers marrying the secrets of winemaking and Lambic blending. Then, in October, he received a decrepit barrel crusted with the remains of a curiosity known as Macvin du Jura, an obscure fortified Vin Doux Naturel from remote Jura, France near the Swiss border. He chose to fill this artifact with a three-year Gueuze blend.

A successful outcome isn’t guaranteed and the production will be maddeningly small, but the young blender’s keen Lambic shepherding skill makes each creative project something to follow. Patiently. ■